Black History Is All Around Atlanta

Flat Rock Archives

Black history is all around us in the metro Atlanta area, but while the attention (justifiably so) is focused on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the King Center, there is a lot of history dating back even before the Civil War. Unfortunately, it’s not so well known, but these sites are great trips for families to learn about and appreciate the journeys of the enslaved and free Blacks struggling to gain their rights.

For instance, we all know that Margaret Mitchell is buried in Oakland Cemetery, but you may not be aware that the cemetery only became integrated in the 1960s. Today, Maynard Jackson, the city’s first Black mayor, is a resident of an integrated cemetery.

Here are a few of the sites that tell the story of Black Atlantans.

Table of Contents

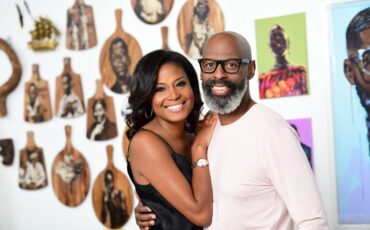

Flat Rock Archives

Located in Stonecrest, the Flat Rock Archives is an African American historical museum that consists of a variety of buildings, including the Flat Rock African-American Cemetery (where 168 people are buried), the T.A. Bryant Sr. House (built in 1917), the Lyon’s House, a barn, smokehouse, outhouse and church. The Lyon House, built in 1821, is the oldest homestead still standing in DeKalb County where people were enslaved. The farm had enslaved people doing a variety of chores, mainly picking cotton or working in the quarry.

Following the Civil War, some 200 former slaves (at least 60 families) stayed in the area and worked on the farms, including T.A. Bryant. In the 1920s, Bryant bought 40 acres of land for $600, and he not only worked the land himself, but leased or sold it to other community members.

“Mr. Bryant was very influential. With his leasing or selling the land, it allowed other family members to earn a living, own land and not have to go up to the north,” says Revonda Cosby, Executive Director of the Arabia Alliance.

It’s interesting to note that T.A. Bryant had a son, T.A. Bryant Jr., whose grandson is the famous comedian Chris Tucker, who has visited the community several times, as well as another cousin, football great Warren Moon.

“Coming to the Flat Rocks Archive is a chance to experience walking into the oldest home in DeKalb County and learn the story of the slaves who worked here,” says Johnny Waits, President and Co-founder of the Flat Rock Archive. “We’re the only Black museum in DeKalb County. We’ve got Black history here. Black history is not taught the way I think it should be. We’re just trying to tell as much history as we can.” $25 for an airbnb tour.

Oakland Cemetery

Oakland Cemetery

Oakland Cemetery was founded in 1850, and the cemetery has sections for people who weren’t white and Christian. The Jewish Flat and Jewish Hill section consists of three Jewish burial areas; the first one started in 1878. There is also the Confederate Burial Grounds where approximately 7,000 soldiers were buried. But for Black History Month, a trip to the Historic African American Burial Grounds is inspiring.

“African American history has such a rich legacy in Atlanta, and it tells the story of racial segregation and injustice,” says Marcy Breffle, Education Manager for the Historic Oakland Foundation. “There’s just so many incredible stories.” Although many of the tombstones are hard to read, the grounds include the burial site of famous Atlantans such as Bishop Wesley John Gaines, who founded Morris Brown College; Rev. Frank Quarles, the founder of the Atlanta Baptist Female Seminary, which grew into Spelman College; and Carrie Steele Logan, who founded the first orphanage for African Americans.

Bishop Gaines was a pastor at Big Bethel A.M.E. church and was enslaved as a child. An 1829 Georgia law prohibited teaching Blacks how to read or write, but he did it anyway. He eventually founded Morris Brown College.

William Finch was born into slavery. After the war, Finch opened a tailor shop, and he became involved in Atlanta politics. In December 1870, William Finch and George Graham became the first African Americans elected to serve on the Atlanta City Council. Known as the “Father of Black Public Education in Atlanta,” he fought to create schools and jobs for African Americans.

The Foundation is offering the “We Shall Overcome: African American Stories from the Civil War to Civil Rights” but it is currently unavailable. There is an abridged version for free.

Smith Plantation

Historic Homes of Downtown Roswell

Roswell, a northern suburb of Atlanta, has a rich Black history that the community and city leaders are working to tell in a more meaningful way. One key illustration of this effort is the annual Roswell Roots festival. This community-wide, month-long festival honors Roswell’s diverse community and celebrates Black History Month. According to their event brochure, “Roswell Roots aims to educate, impact, and promote cultural awareness.” This year’s festival features art, education, and hands-on programs between during the month of February.

While Roswell Roots is several years old, the city’s rich Black history begins in the 1800s. Dating back to 1847, Pleasant Hill Church, a Baptist church was founded by slaves and is still a vibrant congregation today. Many current members of the church have relatives who were brought to Roswell as slaves and are now buried in the church’s cemetery.

Not far from Pleasant Hill Church are a few historic mansions and the remnants of a textile mill that have roots in the era of slavery. Roswell King, the city’s first leader, owned the mill, situated on Vickery Creek, and his slaves helped to build it along with other buildings in the city. The King home, Barrington Hall, which was built in 1830 and features an antebellum garden, is open for tours to the public.

Close by, you will find the Smith Plantation, which was built by slave labor in 1845. The Smith family and 30 of their slaves left two struggling plantations along the Georgia coast to make a new start with 300 acres of cotton farmland north of the Roswell Square. The home is now open to the public as a museum and has many well-preserved features, including servants’ quarters, a cookhouse, spring house, a well and more.

The other historic and likely most well-known of these homes is Bulloch Hall, the childhood home of Mittie Bulloch – the mother of President Teddy Roosevelt. The family home was also inhabited by the couple’s other son, Elliott; he was the father of Eleanor, who married President Franklin D. Roosevelt. On the grounds of this property are slave cabins and a carriage house. Like many establishments, Bulloch Hall is rewriting the history to be more inclusive of the African American experience.

Hooper-Renwick School & Its Community

From its founding in 1944 until 1968, the Hooper-Renwick building was Gwinnett County’s only high school for Black children. While there were other segregated schools that served Black students, this is the only building that is still standing. It will serve as a representation of an era from Gwinnett County’s history.

In 2021, Lawrenceville turned the building and the three acres on which it sits over to the county, and there are plans for a 13,000 square-foot addition with a library and museum, complete with cultural and historic objects and artifacts. The space will also serve as a community center for residents.

The museum will not only tell the story of segregation in schools, but it will also provide a snapshot into the community that surrounded the school, including many churches and Black-owned homes and businesses that are no longer there. Those leading the charge on the Hooper-Renwick School renovation hope the project, expected to be completed in 2023, will bring the community together and enlighten the people of Gwinnett County and the world.

Several miles away from this one-time school, soon-to-be museum, lies what is known as the Promised Land Community. In the early 1900s, many African American families were land owners and residents who helped develop the area. Its residents left a legacy of being industrious and putting a focus on education. The New Bethel AME Church in the neighborhood even served as a school for Black students for many years.

One couple, Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Mitchell Anderson owned and operated the only Black grocery store within the community in the 1930s. In 1970, Thomas and Dorethia Livsey breathed a new life into the Promised Land Community when they opened The Promised Land Grocery Store, which still serves the community today. Members of the Anderson and Livsey families still live in the Promised Land Community, which is seeing a resurgence of interest and is thriving. Gwinnett County even named a new elementary school for the families. The motto of the school “Providing Learning that Lasts a Lifetime” echoes the sentiments of the community’s founders.

-Mary Welch