Literacy Legislation: Read All About It

Only 31% of Georgia’s fourth graders performed at or above grade level in reading in 2022, according to the National Assessment of Education Progress. Metro Atlanta’s scores are in line with the state-wide findings. Look at it another way: 70% don’t read at grade level. Even worse, about 60% of high school students never catch up and graduate (or not) reading below grade level. Such statistics on their own are distressing and coupled with numerous studies that equate reading proficiency with future success, it’s obvious that local schools — and schools across the nation — need to get a better handle on teaching students to read.

“There’s plenty of blame to go around,” says Gary Bingham, interim chair of Georgia State’s Department of Early Childhood and Elementary Education. “Students in Georgia haven’t been doing particularly well for a long time. Underperforming by the third grade is nothing new. The milestones kids were making were wiped out in COVID, especially for kids of color and those in schools with fewer resources. But there has to be a scapegoat, a villain.”

Indeed. Low reading scores, not only in metro Atlanta and Georgia, but throughout the nation, have galvanized parents, academia and teachers but also legislators — all of which play the blame game and have their own opinion on how to effectively teach students how to read.

The state got into the debate last year by passing two literacy bills, House Bill 538 and Senate Bill 211, that established the Georgia Council on Literacy, and requires teachers to have training on “developmentally appropriate evidence-based literacy instruction,” beginning in 2025. Teachers will be trained on the “Science of Reading” as well as requiring schools to screen K-3 students for reading deficiency and issues like dyslexia.

In the upcoming session, a bill will be introduced that would require the state board of education to approve high quality instructional materials for teaching K-3, and to develop training for K-3 teachers on the science of reading, structured literacy and fundamental literacy, among others. Of course, legislating materials and paying for them are two different things, but many involved say that funding will not be an issue.

How Is Reading Being Taught?

So, why are metro Atlanta students flailing at reading? As Bingham noted, fingers are being pointed in lots of places. What happens in the classroom is at the center of the problem and the solution. The issue revolves around the different theories on how children actually learn how to read. The umbrella of reading techniques include those who favor a more structured approach where phonics are the foundation to those who want a more holistic approach, generally referred to as the Science of Reading.

The Science of Reading involves a whole language method that contends that reading is a natural process that students organically pick up with related exposure to words and books and other ways. The science of reading involves language comprehension (background and vocabulary knowledge, language structure, verbal reasoning, literacy knowledge), word recognition (phonological awareness, decoding and spelling and sight recognition) and skilled reading (fluent execution and coordination of word recognition and text comprehension).

Many schools blend both methods but are increasingly putting more phonetics back into the mix.

“You can learn to decode words but not have a rich vocabulary or the skills to reason,” says Ryan Lee-James, chief academic officer at the Atlanta Speech School. The school’s materials note that “reading proficiency is not enough. Only through deep reading — through which we think critically, feel empathetically and take the perspective of others — are we able to become who we are meant to be.”

Leah Matthews put her son in The Schenck School when she saw signs that he wasn’t learning to read in the Atlanta Public Schools system. She wondered about a learning disability, an assertion his teachers dismissed. She had him tested; that lead to a diagnosis of dyslexia, which affects about 15% of the population. “You look at a picture and guess what’s going on. Well, you can guess that the wheels of the bus are falling off by the picture, but what happens when there are no more pictures to guess the context?” she says.

After one year, he returned to public school.

“It was a frustrating process, and I do think the way reading is taught is not beneficial to children with disabilities. There is a sense of reading, but we’ve shied away from phonetics and more than ever populations of people cannot read, especially if you don’t have money to get a tutor or go to fancy private schools.” Virginia-Highland Elementary School even has a phonetic lab, which she supports and believes is the first in the system.

Lisa Morgan, president of the Georgia Association of Educators and a DeKalb County kindergarten teacher, says that students have always learned the reading foundations “but there are new and different ways to teach them.” Still, she says that many reading tools, which involve phonetics, are not being used enough. “You used to have to memorize nursery rhymes. That’s phonetics awareness. We’re not doing that. If the child doesn’t have that basic skill, they’re going to struggle to read.”

Still, she says that “phonetics and the recognition of letters and sounds are only a piece of phonetical awareness. You can sound out a word, but if you don’t know the meaning of that word, it’s not part of your vocabulary, then it’s lost. We have to work on building student vocabulary.”

Other Factors Don’t Help

In addition to the actual reading curriculum, other factors impact the issue.

One is societal. “Like the health crisis, children who are Black, have English as their second language, those who are eligible for free lunches, those in economically disadvantaged communities are more disproportionally impacted,” says Lee-James. “We have generations of people who are struggling because their parents and their parents struggled. These are societal systemic issues.”

Many blame parents for not reading to their children. “The best thing to help your child be a reader is to read to them at home,” says Morgan. “That modeling and reading behavior is so important. I taught kindergarten in a Title One school. The first day a girl told me she wanted to learn to read because her grandmother reads the Bible every day and her granddad the paper. There’s something about at-home reading.”

But, she offers up a reality check. “I’ll go to these meetings about the importance of reading to children at home and what I really want to do is ask parents and others how many books have they read in the past month, the past year? I don’t think a lot of hands would be raised.”

“How do you get students interested in reading?” asks Bingham. “They’re reading a lot less and aren’t interested in reading. We’ve got to address motivation and create a community of learning to read for reading’s sake.”

Others contend that colleges aren’t teaching reading enough or giving student teachers enough classroom training. “There is a considerable spread or variance in the way educators approach reading,” says Bingham. “Some districts have mandated curriculum. Teachers who work in communities of color don’t have the resources of other districts. I don’t like the term ‘science of reading’. It’s the ‘science of literacy.’”

He also says that aspiring teachers are “well trained but most weren’t taught the science of reading nor have a strong understanding of reading. We only have a few classes and hand them off to school districts. We need better partnerships.”

What to Do?

Since reading is a keystone to adult success (according to the National Adult Literacy Survey, 70% of all incarcerated adults can’t read at a fourth-grade level), a concerted effort must be made — and is — to address and change the narrative.

One school district doing just that is the Marietta City school district.

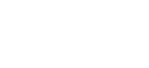

“The district took a hard look at the data and prioritized reading instruction. We drilled down on the data and review it regularly to know where each school stands and where the goals need to be to make sure teaching kids to read is a top priority,” says Jaillene Hunter, a member of the Marietta City School Board of Education and of the Georgia Council of Literacy.

A little more than half of the district’s students weren’t up to grade level and “we needed to find out why so many weren’t reading. We made the decision to invest in our people, not ‘a program.’ We are training our teachers to understand why they’re teaching the science of reading and how. We’re still learning, and we don’t have all the answers, but the teachers are the heroes here.”

Students are given explicit and systemic instruction on reading and taught a specific reading skill set — repeatedly — until the student grasped it. Another important element was regularly gauging a student’s progress. “The state doesn’t test for reading comprehension until the third grade. You don’t have a picture of where a student is until third grade and by then the chances of getting up to grade level are slim.” Marietta City Schools test three times a year and if a problem is identified, they teach directly to the student.

The schools also have what it calls the 90-10-5, which is 90 minutes of reading instruction a day; a 10-1 student-teacher ratio for all students and those who aren’t at grade level are pulled out for smaller classes for all five days of the week.

In addition, the district was “very honest with parents and said we’re putting our time and money into this — a reflection of our values — and we needed them to make the same investment at home. We also told them that tutoring was important and that we needed their child to stay after school for tutoring. It was important to partner with parents.”

While it is only in its third year, the district is putting its money where its mouth is. They spent $6.2 million for reading specialists, supplements and supply teachers; $2.5 billion via the Joseph B. Whitehead Foundation for curriculum resources, facilitators and substitute teachers and $1.2 million on after-school and break training, as well as remediation and summer school.

Simpson Elementary School in Peachtree Corners has 90% or more of its students reading at or above a third-grade level. The Gwinnett Schools use the Scarborough Reading Rope, which hones in on both language comprehension (verbal reasoning, language structure, vocabulary, background and literary awareness) and word recognition (phonemic awareness, decoding and sight word recognition). They also have programs for early intervention for struggling students.

“We want all children to read and comprehend on grade level,” says Morgan. “We want to give them the best teachers and the best way to be taught. It is however not enough to focus on literacy in our schools. We have to focus on literacy in our homes, community and we have to once again make literacy a priority in the classroom.”

Bingham says it can be done but “you’ve got to identify it as a priority and make the legislature work with educational partners to identify and study what kind of legislation should pass. Good things are created by dialogues of what we should be doing, what is not working and then you have to put thoughtful money behind it.”

Adding, “A good investment will likely pay off in dividends.”

-Mary Welch