Understanding Dyslexia

Dyslexia is one of the most common learning differences. Often misunderstood as a problem with intelligence or vision, dyslexia actually stems from neurological variations in the brain’s structure and function when it comes to language processing. Brain imaging and cognitive science studies have improved understanding on how dyslexic brains work, offering insights, challenging outdated myths and paving the way for more effective strategies.

What Is Dyslexia?

Dyslexia is a diagnostic condition. Professional evaluations test your child’s skills, and a diagnosis can be used to advocate for the student to get her the accommodations she needs.

“Dyslexia is not a general term that can be used for all kids who can’t read,” Brenda Fitzgerald, the Executive Director of Georgia Educational Training Agency. “It’s a very specific diagnosis, and it’s for kids who have difficulty breaking the code with reading, writing and spelling.”

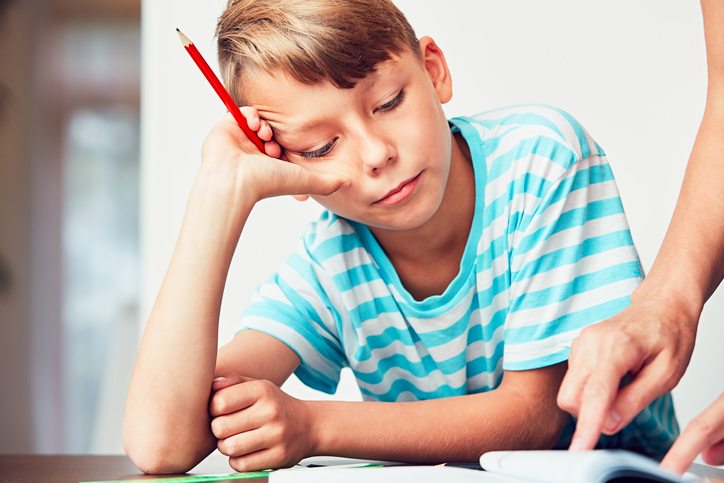

A person with dyslexia struggles to accurately and fluently read and spell words. The literacy process isn’t automatic for him, so it can take him longer to process information.

“Dyslexia is a result of a difference in the wiring and processing of those neuropathways in the brain’s reading and language functioning,” Fitzgerald says. “A dyslexic student has difficulty holding the correct sound long enough to connect it to the part of the brain that matches the sound to the letter. This can affect reading, writing and spelling.”

Reading and the Brain

“Reading is very new in the brain. We don’t have an area solely dedicated to reading. We have areas to help. The network in the brain utilizes a bunch of other systems — language, attention, memory,” says Dr. Nikki Arrington, Assistant Research Professor in the Department of Psychology at Georgia State University.

Children with dyslexia process information differently, a phenomenon that is still being researched.

“Reading and language is processed in the left hemisphere, and the four regions — frontal, parietal, temporal and occipital — work together to recognize words for reading, spelling and understanding,” says Jenn Parks, the Structured Literacy Coordinator at Saint Francis School. A functional MRI (fMRI) is a type of scan showing which areas of the brain are most active. “There are fMRIs of children with dyslexia and children without dyslexia, and when they’re given the task of reading, the brains of children with dyslexia are not activating all four lobes.”

Reading is a complex task requiring different areas of the brain to work together to recognize and interpret words. For a learner with dyslexia, this task is even more complex.

“You’ll see less activation in the areas of the brain that we see in typical readers, specifically in the areas of the brain that map sound onto written language,” says Dr. Rachael Harrington, a clinically trained speech-language pathologist, neuroscientist and Assistant Professor in Georgia State University’s Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders. “We see increased areas in the right hemisphere, which is a part of the brain that is not usually involved in reading.”

A 2020 “Asian Journal of Psychiatry” study showed participants with dyslexia used areas in the brain more involved in recalling memory. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), a neuroimaging technique for white matter microstructure, has shown widespread disrupted structural brain connectivity with reading impairments, according to a 2019 “Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience” study. Both accuracy and processing speed are related to white matter, while reading processes are related to the development of gray matter volume and cortical thickness.

Literacy Learning

Dyslexia can affect any or all of the processes regarding reading, writing, spelling or comprehension.

“When you’re looking at a word, you have to identify the letter, connect it automatically to a sound and blend it together for the word. The brain also has to function in the opposite way. You hear the word, segment the individual sounds, associate those with a letter and write down the word,” Parks says.

To make it more complicated, English doesn’t have a one-to-one relationship with a letter and a sound. Instead, there are multiple ways to create the same sound. “If the brain is working really hard to read or spell a word, it doesn’t have enough time to construct meaning,” Parks says.

Literacy skills build on top of each other. “With early literacy skills, you’re learning: this is a book; this is how you hold a book; you read it from left to right. With the early reading phase, you’re mapping the sounds onto letters, learning phonics instructions and building vocabulary,” Harrington says. “When other students are moving on to reading to learn with a science or history book, these kids are still a step behind.”

Dyslexia is not due to a lack of intelligence, and with appropriate remediation, a student can learn how to make these connections in his brain and build these skills.

“In the brain of kids with dyslexia, we see structural differences in those parts of the brain to help support reading,” Arrington says. “With reading intervention programs, normalization occurs. This is a lifelong difference in your brain. It doesn’t make you less; it just means your brain functions differently.”

How You Can Help Your Child

If your child has been recently diagnosed with dyslexia, you’re likely looking for the best ways to help her move forward in her educational journey.

A cure for dyslexia doesn’t exist. “You can’t cure a way that your brain has developed,” Harrington says. “You can train it, but there is no magic pill that’s going to change the structure of the brain.”

Because of research, we know how to help children with dyslexia learn.

Start remediation early. According to a 2019 study in “Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience,” early remediation takes advantage of the brain’s plastic state when white matter is still developing.

“Remediating early is critical,” Fitzgerald says. “Dyslexia can’t be cured, but it can be remediated well. When you delay remediation, it’ll bleed over into those other domains — emotional, social, cognitive, language, motor.”

At public schools, the state of Georgia has legislation requiring universal dyslexia screening for students in grades kindergarten to third to help ensure early identification and intervention.

Find a school using a structured literacy program, such as Orton-Gillingham and Wilson, that targets different aspects of reading and language development.

“A structured literacy program is an evidence-based researched instructional approach that teaches reading and writing skills explicitly and systematically,” Fitzgerald says.

“Structured literacy focuses on two things: content and the principles of instruction. This means the what and the how,” Parks says. “At Saint Francis, we teach very clearly and directly what a rule is. We’re not leaving things up for students to discover on their own. We make sure the skills are mastered, not just introduced. Instruction is multisensory and hands-on, so students are actively engaged. They’re moving letter tiles to build words, making motions when learnings sounds, color coding to understand syllables or using cards to build sentences. Our instruction tomorrow is informed by what happens in the classroom today.”

Celebrate your child’s strengths and acknowledge her accomplishments.

“They’re amazing. They think outside the box. They have compassion for other people, because they’ve felt what it’s like to feel different. Their thinking and reasoning isn’t compromised, and they’ll excel in the arts, math, sports, science. They’re super creative. They take in a lot of information and perceptional reasoning,” Fitzgerald says. “These students can go onto be entrepreneurs, surgeons, architects — whatever they want to be they can be.”

Check out available resources through International Dyslexia Association Georgia, Georgia Educational Training Agency, Decoding Dyslexia and Orton-Gillingham.

-Emily Webb

Signs of Dyslexia

For a comprehensive list of warning signs, the Mayo Clinic and the Yale Center for Dyslexia and Creativity are excellent resources.

- Late or delayed speech

- Difficulty rhyming

- Mispronouncing familiar words

- Difficulty learning and remembering letters of the alphabet

- Difficulty sounding out simple words

- Complaining about reading being hard

- Avoiding reading out loud

- Family history of reading problems

Learn the Lingo

Dyslexia: A specific, neurobiological learning disability characterized by difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition and by poor encoding (spelling) and decoding (reading) abilities.

Dysgraphia: The condition of impaired letter writing by hand. Impaired handwriting can interfere with learning to spell words in writing and speed of writing text. Children with dysgraphia may have only impaired handwriting, only impaired spelling or both.

Dyspraxia: Refers to trouble with movement, including fine motor skills, gross motor skills, motor planning and coordination.

Dyscalculia: A condition that makes understanding numbers, performing calculations, counting, and basic arithmetic skills difficult.

Neurobiology: The study of cells of the nervous system and the organization of these cells into functional circuits that process information and mediate behavior.

Phoneme: Identifies the smallest unit of sound, such as “b,” “t” or “tch.”

Phonemic Awareness: The ability to manipulate phonemes. Dyslexic students usually lack phonemic awareness and may be unable to identify phonemes within words.

Grapheme: Individual letters and groups of letters that represent single phonemes.

Orton-Gillingham Approach: Orton-Gillingham was the first teaching approach designed to help struggling readers by explicitly teaching the connections between letters and sounds, and it was created in the 1930s by neurologist Dr. Samuel T. Orton and educator and psychologist Anna Gillingham. The approach combines multi-sensory teaching strategies with systematic, sequential lessons focused on phonics.

Wilson Reading System: A structured literacy program based on phonological-coding research and Orton-Gillingham principles that directly and systematically teaches the structure of the English language. Students learn fluent decoding and encoding skills.

Lindamood-Bell Learning Processes: Programs to develop the sensory-cognitive processes that underlie reading and comprehension.

Fast ForWord: An adaptive reading and language program channeling neuroscience to provide results for struggling learners.

Barton Reading & Spelling System: A tutoring system for those who struggle with spelling, reading and writing due to dyslexia.

Adapted from understood.org, disabledworld.com, ldonline.org, ldaamerica.org, sciencedaily.com, readingdoctor.com, orton-gillingham.com, wilsonlanguage.com, lindamoodbell.com, bartonreading.com and dyslexiaida.org

Find a list of schools that support dyslexic students in Atlanta Parent’s Dyslexia School Directory.